Today we’re reading Anton Shammas’ Arabesques, originally published in 1986, and recently re-published by NYRB in 2023. It was written by Shammas in Hebrew and translated to English by Vivian Eden.

Amidst my search for more Palestinian literature last October, I came across Anton Shammas’ Arabesques, a novel that seemed as if it could fill a perspective gap: that of the Christian Palestinian, and the Arab Israeli.

Communities of all Abrahamic religions co-existed in the land of Palestine long before Israel. And during the Nakba of 1948, all Palestinians (the Indigenous people) were subjected to the violence, regardless of faith (the more pertinent element to the settler-colonial project here is anti-Arab racism). But the limiting binaries injected through mainstream, modern-day “explanations” of this history do not leave room for people who do not fit neatly into the narrative—framed simply, and incorrectly, as Jewish/Israeli vs Muslim/Palestinian, though in actuality, these things are not synonymous. The truth has been collapsed—or you know, completely revised.

So I was intrigued by the synopsis of this “novel” because it chronicled a Palestinian Christian family before and after the Nakba, and brought this exact problem (of identity) to the fore. That meant another perspective to add to all of the books I’ve read about Palestine, and so I picked it up.

“Uncle Yusef used to say, It is better for a story not to be told, for once it is, it is like a gate that has been left ajar.”

Review

Shammas uses the ornamental arabesque as narrative form for his novel about family history and dissected identities, as an Arab-Christian-Palestinian-Israeli. An array of characters, histories, times, and places weave in and out of each other, in a way that makes little sense until you step away from the individual lines.

He pulls from both oral storytelling (of the past) and post-modernism (of the present—in the 1980s) for a unique literary style that places Palestinian history in the cultural contemporary, closing the gap created by decades of Zionist revisionism.

To add another formal layer, the novel is split into two distinct sections: “The Tale” and “The Teller”. This choice leads to a deft interweaving of the autobiographical and the meta-fictional, the past and the present, the traditional and the modern.

In “The Tale”, we are presented with the histories of The Character’s family and village life; in “The Teller”, The Author interjects on the construction of the story, as he battles with identity, memory, and narrative agency. All the while, The Author is attending an International writer’s program in the U.S., populated with a group of characters who seem to be stand-ins for their own national identities.

His presentation of “The Tale” alludes to oral storytelling: the way stories are passed from generation to generation, told and re-told, embellished or changed in some way upon retelling. Information (family stories, relationships, beliefs, moralities, history) are shared in this manner, though often the meaning of a story isn’t clear in the moment. It is the interconnecting of stories that creates clarity and meaning, long after the fact, after stepping back to see the pattern.

His presentation of “The Teller”, meanwhile, utilizes typical post-modernist elements: detached irony, caricatured representations, metafictional musing, unreliable narration, and simmering self-loathing mangled with disconnected identity. A mirrored/doubling motif runs through, commenting on the bisected identities at the center of the entire project.

The Christian, The Arab, The Palestinian, The Israeli, The Refugee, The Intellectual, The Exile, The Author, The Character, The Character within The Character…

Born into a place where many of these identities are solely defined against each other—and moving through the literary world, where the others have their own meta contentions—Shammas neither tangles nor disentangles the list. He simply contends with the complexity of intertwining realities as they are, and subtly points at the erasure of those intersections.

“I’ll write about the loneliness of the Palestinian Arab Israeli…”

The Israeli Arab

Arabesques is also a response to modern Israeli literature, its representation of the Arab figure, and the cultural erasure of the Arab Israeli—as well as every other iteration of entangled identities in the region. Shammas himself can be categorized as Palestinian, Christian, Arab, or Israeli by turn (and much more), but his family has a history that exists outside of such narrow labels—a history that existed long before such labels became contentious. Through this novel, he foregrounds the history of the culturally-sidelined, and presents the literarily-erased “Arab” directly to those who have done the erasing. Shammas’ decision to write this work in Hebrew—being the first Arab to write and publish in Hebrew—was considered controversial. But writing in Hebrew put this book directly into Israeli literary culture, precisely at the site of contention.

In the Yale Review, Ratik Asokan discusses this aspect of Shammas’ work in enlightening detail—much more intricately and knowledgeably than I ever could.

Quotes

“Something in their tortured expression gave me the feeling that it would have been better if the story had remained curled up like a caterpillar in the cocoon of silence forever. But now that the cocoon had hatched and the butterfly of the story, with a magical flick of its wings, had shaken off the webs of years of forgetfulness, the way backward was closed both for me and for the butterfly.”

“Once again I stand at the gate that is ajar. Now that my life is has followed the course of this winding arabesque, I find myself once more at the place where I started, as if that flight from the village of Khabab in southern Syria back in the 1830s, had been a foreshadowing of the real journey that awaits me now.”

“This was the uncertainty which is an advantage that the dead have over the living—the dead who rise to buffet you when you are indifferent to the twists and turns of the present but are made to realize you are still vulnerable to the caprices of the past.”

“In case the only reality was dust returning to dust and the jaws of the beast of nothingness gaped wide, he still could believe that the circular, the winding and the elusive had the power to resist nothingness.”

Further Reading

On Anton Shammas's "Arabesques": Revisiting the first major book in Hebrew by an Arab writer by Ratik Asokan

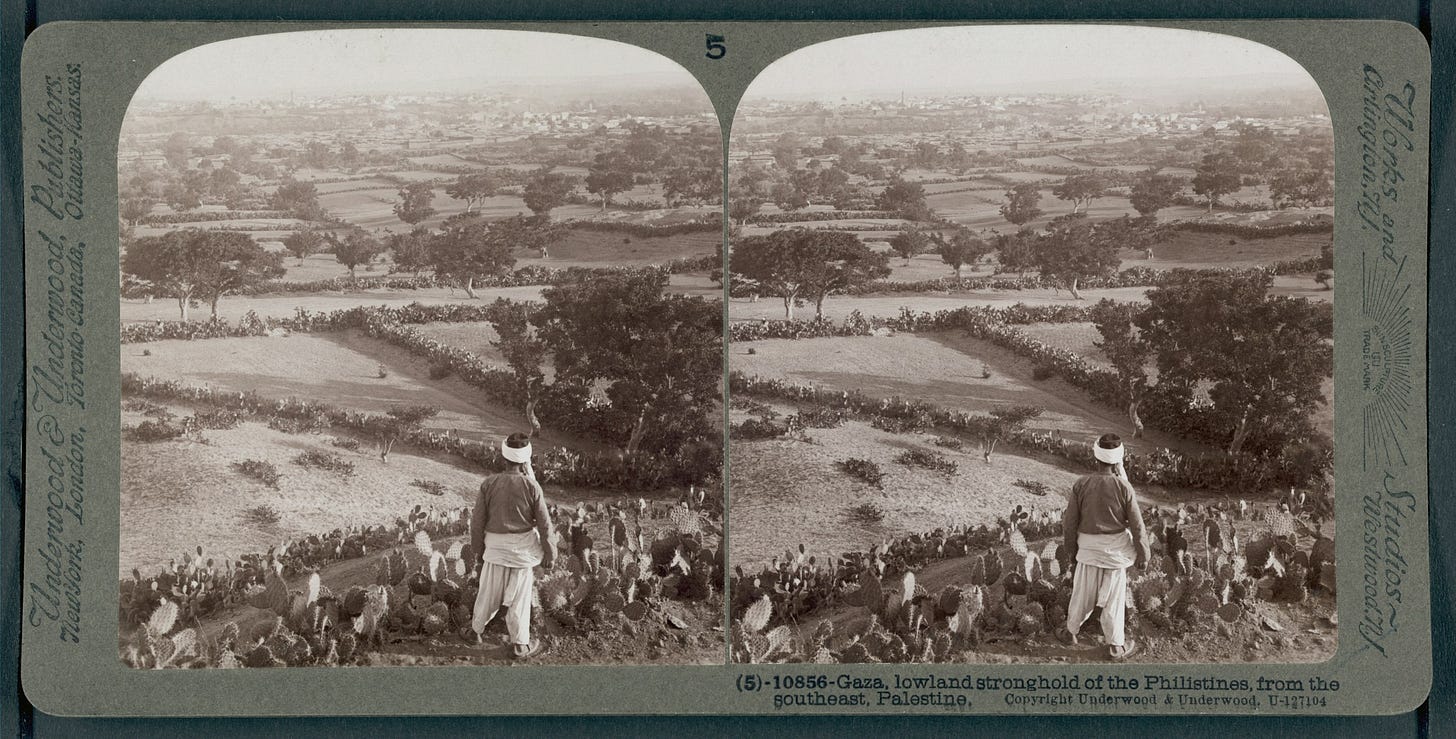

These Stunning Images Show Palestinian Life Before the Nakba on Jacobin

Thanks for reading today’s issue of Empty Head! More essays, reviews, and other musings are on the way. Follow me on Instagram and Storygraph for more reading updates! Be sure to subscribe so you don’t miss anything.